Classifying the World’s Soils

Across the planet there are a wide variety of soils which vary with climate, topography, vegetation, geological substrate, and age (Jenny, 1949). The process of soil development is called pedogenesis, and it is the unique pathway of a soil’s development that shape its capacity to retain nutrients, water and sustain life. Just as plant and animal biodiversity is important to sustaining overall ecosystem health, the biodiversity of the world’s soils across the Earth’s skin are essential to providing unique ecosystem services that support plant and animal life.

As in the Linnaean classification system, soil scientists have worked to group together soils with similar characteristics. There are several classification system for soils including the Canadian and Australian classification systems among others. However, the two most widely utilized taxonomic systems are the World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) and USDA soil taxonomic systems, developed by the International Union of Soil Sciences and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, respectively. The WRB taxonomic system includes 32 different reference soil groups and is utilized across many European nations and other countries across the world. The USDA Soil Taxonomy has 12 soil orders and is mostly applied in the United States of American. Each order is differentiated by one or more dominant physical, chemical, or biological properties.

Figure 1: The Global Soil Regions map using the USDA 12 order soil taxonomy system. (NRCS)

Figure 1: The Global Soil Regions map using the USDA 12 order soil taxonomy system. (NRCS)

Further Resources

Check out this link to explore the USDA 12 soil orders of Soil Taxonomy

To explore the 32 orders of the World Reference Base classification system, click here

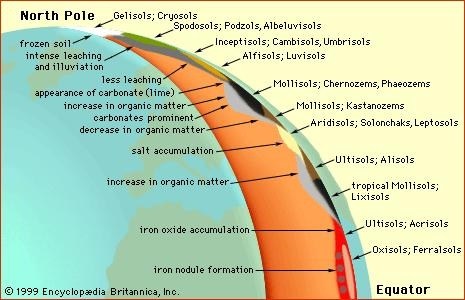

*Figure 2: Soil types in the Northern Hemisphere according to WRB and USDA taxonomy, their distribution by latitude, and the accompanying influential soil forming processes.

*Figure 2: Soil types in the Northern Hemisphere according to WRB and USDA taxonomy, their distribution by latitude, and the accompanying influential soil forming processes.

Pedogenesis

Pedogensis is the process of soil formation resulting from the influence of environmental factors across time. The five main factors of pedogenesis are, climate, organisms (including humans), relief, parent material, and time (Jenny, 1949). Commonly referred to as CLORPT, these factors along with their processes of additions, removals, transfers and transformations create the attributes of each pedon, including soil type (classification), physicochemical qualities and suitability for particular uses.

Soil = f(cl, o, r, p, t, …)

Each combination of soil forming factors results in a unique soil type. An example would be that arctic soils develop in glacial deposits and are heavily influenced by freez/thaw cycles, resulting in strong mixing due to frost heave and the incorporation of ice layers into the soil profile. In contrast, tropical soils on the other hand can be formed by different parent material of volcanic origins (although not all volcanically derived parent material is in the tropics) that has been heavily weathered by the intense rainfall in these regions, as a result these soils are deep, organically-rich and contain an abundance of secondary minerals. It is the combination of contrasting factors and processes that give the Earth its unique soils.

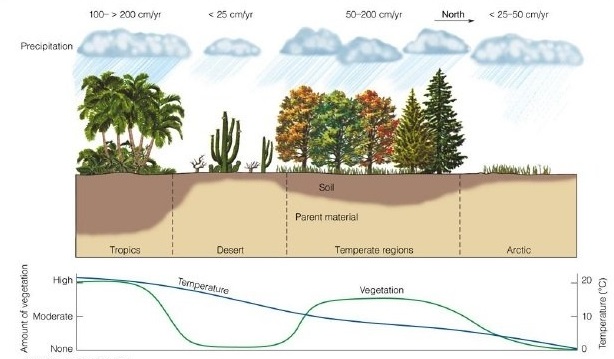

Why do we care about soil diversity? Soils are the second most important influence on vegetation after climate. To understand the link between climate and vegetation see the previous blog post titled “Climate and Plant Distribution” (Link to GW and PL blog post 2aiii). The fertility of the soil along with the climate determine the type and density of aboveground biomass for a region. In Figure 3 below the vegetation type, temperature and precipitation regime are categorized along a gradient below.

Figure 3: The effects of climate on soil formation and dominant vegetation type.

Soils are he second most important influence on vegetation after climate (Thomson Higher Education (2007)

Figure 3: The effects of climate on soil formation and dominant vegetation type.

Soils are he second most important influence on vegetation after climate (Thomson Higher Education (2007)

The density of aboveground vegetation, roots and their turnover all influence the abundance and cycling of soil organic matter. Looking back at Figure 2 we can see that tropical and temperate regions contain more soil organic matter than desert and arctic regions. This phenomenon is due to the higher density of vegetation in these regions, which is associated with larger inputs of organic matter to soils. These organic deposits decompose and become incorporated into soils. This carbon storage is an example of an ecosystem service that soils provide. Carbon dioxide is taken up from the atmosphere by vegetation and deposited belowground in the form of root and root exudates. Carbon is also deposited in the soil in the form of dead fauna. This carbon is then stored until it is respired by microorganisms back into the atmosphere.

Further References:

Bockheim et al. 2014 doi

Van Cleve and Powers Chapter 9, 1995 doi

Importance of unique soils to ecosystem services

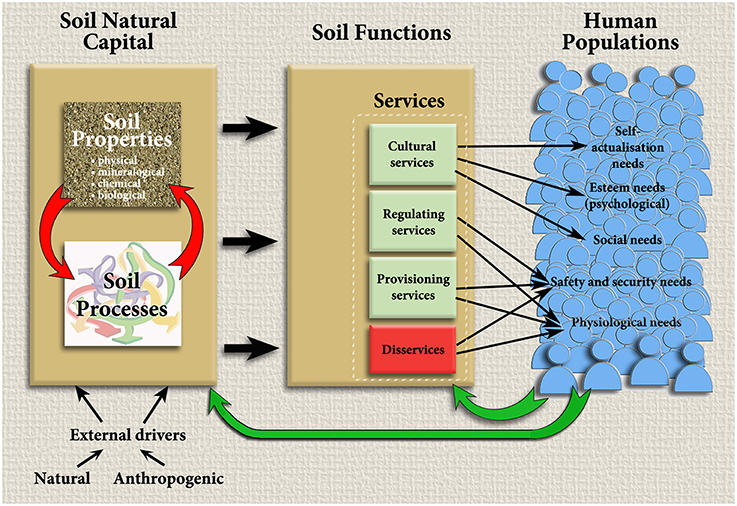

Soils provide many crtical ecosystem services. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment defines ecosystem services as, “…the benefits people derive from ecosystems.” Basically these are the services that the Earth provides for free, and most people live their day to day lives without even thinking of them. Ecosystem service benefits fall into four main categories: supporting, provisioning, regulating and cultural services. Supporting services are necessary for the functioning of all other ecosystem services, provisioning services provide food, water and raw material to humans, regulating systems control the quality of air, water, climate, pests and disease, and cultural services provide spiritual, recreational, aesthetic enrichment. These services vary among ecosystems, but all have one thing in common, humans need them in order to survive.

Figure 4: The proponents to ecosystem services from soil and how they provide to human populations. Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (2005)

Figure 4: The proponents to ecosystem services from soil and how they provide to human populations. Millenium Ecosystem Assessment (2005)

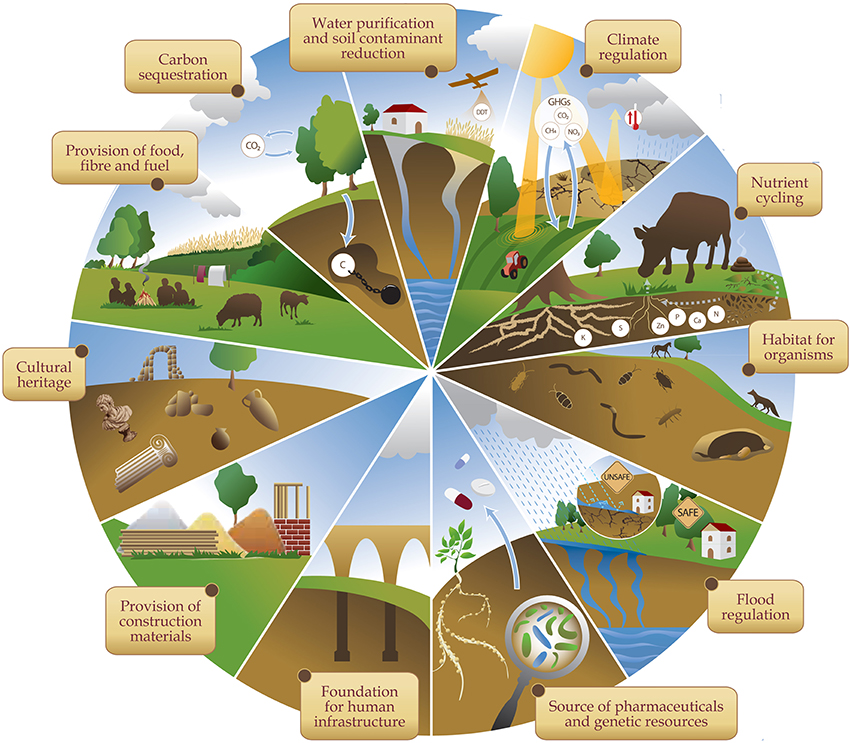

Some of the ecosystem services provided by soil (or that involve soil) are listed from the IPCC 2002 report:

- Clean air & water

- Cultural, spiritual & recreational values

- Decomposition and cycling of organic matter

- Gas exchange and carbon sequestration

- Maintenance of soil structure

- Medicines

- Plant growth control

- Pollination

- Production of food, fuel & energy

- Regulation of nutrients and uptake

- Seed dispersal

- Soil detoxification

- Soil formation & prevention of soil erosion

- Suppression of pests and diseases

Who knew that soils have been under our feet this entire time providing most of the means we need to live?! Clearly this a lengthy list of services, all important for sustaining life. We need soils for the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we consume, and everything in between. Without healthy soil there cannot be healthy ecosystems, and in turn a healthy global human population.

Figure 5: The main ecosystem services provided by soils (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

Figure 5: The main ecosystem services provided by soils (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

"The nation that destroys its soil, destroys itself." -Franklin Delano Roosevelt

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 60% of ecosystem services are being degraded or used unsustainably. Nonlinear changes in ecosystem services include accelerating, abrupt and potentially irreversible changes to ecosystems. These nonlinear changes are becoming more and more common as climate change comes to the forefront as one of our greatest global issues. Due to the unpredictable nature of these changes it is nearly impossible to predict these events through modeling. Therefore the human capability to adapt are inhibited (See blog post titled Global Carbon Modeling to understand more about these abrupt changes and threshold modeling for climate change (Link to 2av.post)). One of these nonlinear responses to increased fossil fuel emissions is the change in the atmosphere’s capacity to cleanse itself from potent greenhouse gases. The overwhelming amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is inhibiting the Earth’s capability to regulate its global air temperature. Scientists have been heavily focused on this nonlinear change since the 1980s. Soils may hold some of the keys to helping regulate the carbon within the atmosphere. Without managing these soils properly we could have more issues in the future with ecosy

Connecting back to soil properties, each unique soil type provides particular ecosystem services to the biome it is a part of. For example, soils in tropical climates, that have volcanic parent material, hold special physical and chemical properties that make it able to sequester carbon better than other soils by creating aggregates that make the carbon inaccessible to microbes. If the microbes cannot access the carbon in the soil then they cannot respire it and it stays in the ground rather than going into the atmosphere. This property is unique to volcanic parent material because of the role that iron and aluminum organo-mineral particles play in stabilizing the aggregates. This makes these tropical soils important to ecosystem services involved in the global carbon cycle.

Further References:

Millenium Ecosystem Assessment link

Clothier et al. 2011 doi

Baveye et al. 2016 doi

Soils and carbon sequestration: Locking up greenhouse gases underground

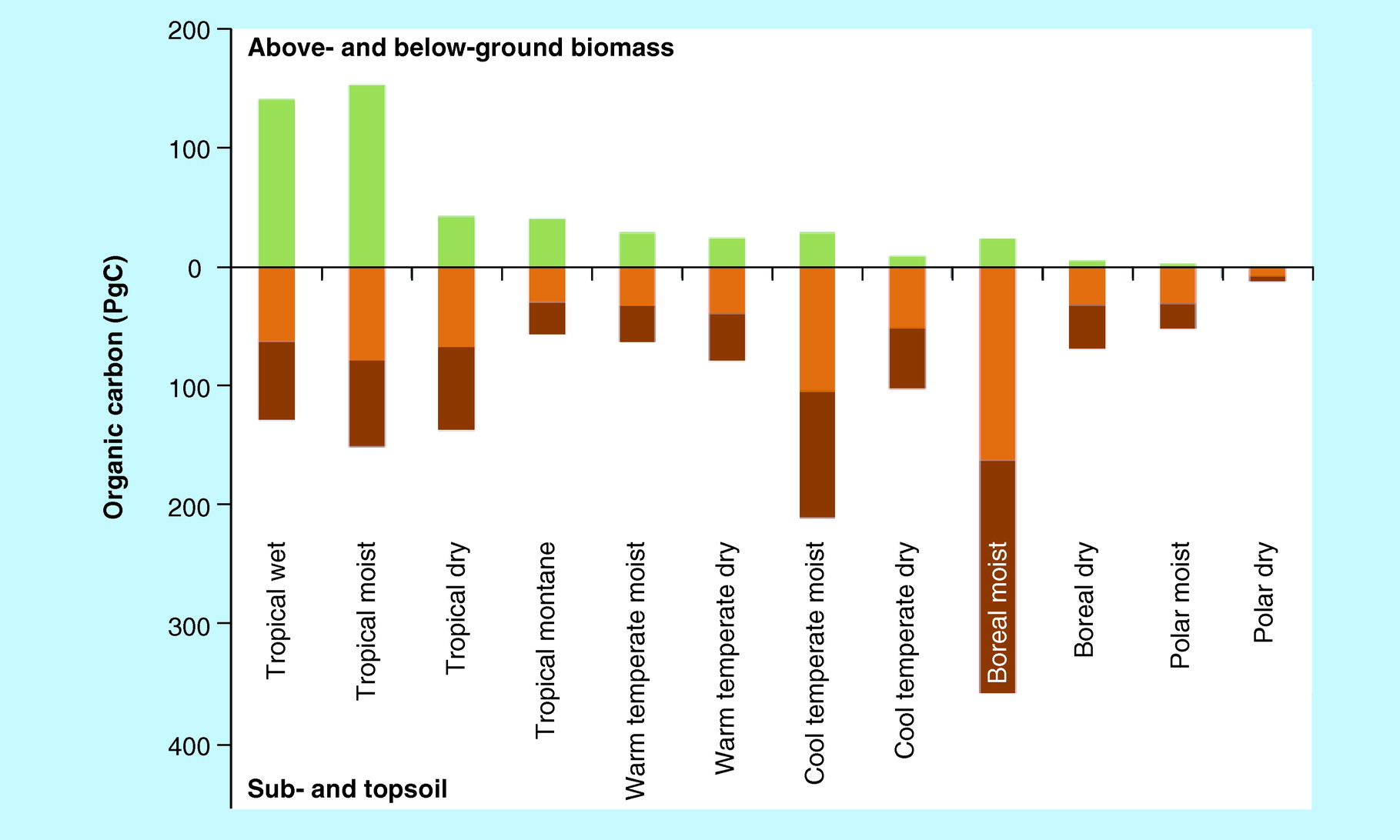

Sequestration of carbon is one of the biggest ecosystem services provided by soils. While there is carbon above ground that you can see in the form of vegetation, there is also a large amount of carbon below ground. Soils hold ⅔ of the world’s carbon found in terrestrial ecosystems. Carbon from the atmosphere is incorporated into vegetation through photosynthesis and then is introduced to soils through roots and decomposing organic matter. This organic matter (carbon) will either stay in the soil or be respired back to the atmosphere (link to post 1 (susans)).The amount of carbon allocated to each ecosystem is dependent on climatic controls, such as precipitation and temperature as well as soil characteristics such as pH and mineral assemblage. See Figure 6 below from Jackson et al. (2017) to understand how much carbon is above and below ground for each ecosystem.

Figure 6: The amount of carbon above (green) and below ground biomass (topsoil = orange, subsoil = brown) for each biome. (Jackson et al., 2017)

Figure 6: The amount of carbon above (green) and below ground biomass (topsoil = orange, subsoil = brown) for each biome. (Jackson et al., 2017)

From this figure we can see that warmer wetter climates hold more organic carbon in their aboveground biomass, while colder, wetter climates hold more carbon in their belowground stocks. This large amount of below ground organic carbon in the colder, wetter region of boreal moist biomes is where microbes decompose the organic matter within the soil at a slower rate, therefore more organic matter can accumulate. With rising global temperatures the soil thaws and activates the more microbial activity within the soil. These now mobilized microbes start to decompose the carbon within the soil and the carbon is respired as the greenhouse gas, CO2. This creates a positive feedback loop that accelerates the consequences of climate change.

Learning to manage carbon sequestration in soils as an ecosystem service is critical for the health of our planet, especially in the midst of climate change. By properly managing each soil, for each specific ecosystem, we can study how we may be able to incorporate more atmospheric carbon in soils, provided the greenhouse gas effect does not overwhelm the mechanisms protecting carbon from biodegradaion in each ecosystem first. From tropical soils using volcanic minerals to stabilize organic matter, to arctic soils losing their ability to freeze microbial activity, the difference in challenges facing soil carbon sequestration varies by biome type. By using global models we can try to predict the focal areas that could benefit from land management changes which could subsequently dramatically alter the amount of carbon in the atmosphere. (link again to 2av.post)

Further Resources:

Jackson et al. (2017) doi

Vitharana et al. (2017) doi

Raich et al. (2006) doi

Torn et al. (2005) doi